Elizabeth returned to New York in the summer of 1851, where she would tirelessly pursue her pioneer work for the next seven years. She set up a practice, but received few patients. The medical profession was detached, and the people of the city were skeptical about coming to a woman for medical help. She applied to a City dispensary in the hopes of serving as a physician in a woman's department, but was refused. Instead, she set up her own clinic in a poorer section of town. She still had to deal with slanderous gossip and disrespectful letters, and at times the sense of loneliness threatened to overwhelm her. In the fall of 1854, she adopted an orphan girl, whose presence encouraged her and brightened her days.

In the meantime, her sister Emily had also managed to graduate from medical school and studied abroad in Europe for a time, and she joined Elizabeth in New York in 1856. Another woman, Dr. Maria E. Zackrzewska, joined them straight out of medical college, and together the women rented a house and set it up as a hospital. "The New York Infirmary for Women and Children" had officially opened -- and met with heavy opposition. The practitioners of the Infirmary were all women; however, a "board of consulting physicians" (comprised of prominent men of medicine) did add prestige.

In 1858, Elizabeth headed to England to see what possibilities it offered women in the medical field. While there, she was recognized as a physician in England, and became the first woman to have her name placed on the Medical Register of the United Kingdom. This time, society seemed more welcoming and accepting.

By the time Elizabeth returned to New York in the fall of 1859, the funds for their infirmary had grown to the point that they were able to purchase a spacious house and convert it into a hospital. The work continued to grow, but soon efforts would be interrupted by the outbreak of the Civil War.

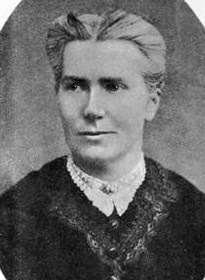

|

| Elizabeth's sister, Dr. Emily Blackwell |

In 1858, Elizabeth headed to England to see what possibilities it offered women in the medical field. While there, she was recognized as a physician in England, and became the first woman to have her name placed on the Medical Register of the United Kingdom. This time, society seemed more welcoming and accepting.

By the time Elizabeth returned to New York in the fall of 1859, the funds for their infirmary had grown to the point that they were able to purchase a spacious house and convert it into a hospital. The work continued to grow, but soon efforts would be interrupted by the outbreak of the Civil War.